These are a Few of my Favourite Lyrics

(Ten, to be exact)

2024 has been a thin year for this blog. Here is an entirely subjective, highly arbitrary, somewhat dubious list of ten of my favourite lyrics.

First, a little about the methodology. I’ve focused on theatrical or theatre-adjacent songs. I’ve tried to avoid anything screamingly obvious. I generally have a preference for colloquial language over anything poetic (more on this later). And I’ve tried to select examples that, for me, highlight different ingredients that go into a kickass lyric.

There are glaring omissions. I’ve culled songwriting titans for many reasons – because they’re too well-known, or because their work is so flawless and natural that it ceases to be recognisably theirs, or because I just wanted to highlight someone else. There’s a skew towards the contemporary. Also, no personal connections. I have friends and mentors who’ve written lyrics I find miraculous, but I’ve left them off the list – except in one case.

(1) The Character Establishment Lyric — from “It All Comes Back” (Fun Home)

Where better place to start than with an opening number?

I saw Fun Home at the Young Vic in 2018. The run was entirely sold-out, but I phoned the box office and by chance they had a last-minute return: back of the balcony, partial vision, £15. Quite literally the best £15 I’ve ever spent.

It’s an utterly remarkable musical. Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori weave together dialogue and song snippets to devastating effect. Musical motifs are integrated into the script; reality melds with fantasy. In an age of “by the playbook” musicals, Fun Home radiates originality, almost as if it came from a parallel universe whose theatrical conventions had evolved differently. (Instead of an “I Want” song, we get a “He Wants” song; instead of a single actor playing multiple parts, we get three playing the same character, albeit at different ages.)

At the beginning of the musical, middle-aged cartoonist Alison Bechdel is trying to piece together her memoir. She recalls a moment from her childhood when her father, Bruce, took her through a box of “junk” that he’d picked up from a neighbour’s barn. We witness the memory unfold onstage. The contents of the box seem worthless, until Bruce comes across a treasure and sings to her:

Linen.

This is linen.

Gorgeous Irish linen.

See how I can tell?

Right here, this floating thread, you see —

That’s what makes it damask.

I’m no great expert on linen. I have a very hazy idea of what a floating thread is, an even hazier one about damask, and no clue as to how the two relate. Even after reading the lines, I’m not much the wiser. But I do suddenly know a lot more about Bruce Bechdel:

He knows a ton about fabric – its quality, its provenance etc. He speaks with the vocabulary of a specialist.

Not only does he know about it, he cares about it (“gorgeous”). He recognises and values class.

He also cares about educating his young daughter. Rather than pushing her away, he invites her to share in his haul, his delight, his expertise. He wants to instil his values in her. (He seems to like her, at least in moments like these.)

(Inference) He’s not rich. Rather than buying high-end linen at market price, he combs refuse from his neighbour’s barns for hidden gems.

(Inference) He’s not like the other dads. He recognises qualities that elude others. His personality may even be borderline obsessive.

All this from so little. Lisa Kron brilliantly demonstrates that it often doesn’t matter if the audience doesn’t understand exactly what a character is talking about. The important thing is that the character understands. And then we can better understand them.

(2) The Funny Lyric – from “A Little Upset” (Cry-Baby)

Musicals should be funny! Not just witty or cute or clever; the audience should repeatedly laugh out loud, en masse. (I’d contend that every single first-rate musical achieves this.)

So how to select just one lyric? Throw a dart at the score of shows like Guys and Dolls, Fiddler on the Roof, Legally Blonde, The Music Man etc., and you’ll land on a great joke. Let me offer up an example from a criminally underrated show, Cry-Baby.

Ruder, funnier and darker than its cousin Hairspray, Cry-Baby is a smorgasbord of fantastic lyrics. (The first line, embodying the peppy, preppy sensibilities of 1950s Baltimore: “It’s a beautiful day for an anti-polio picnic!”)

At this point in the show, hero Wade “Cry-Baby” Walker has been wrongfully imprisoned and is beginning a dance-number-turned-escape. The tone is menacing. Backed up by his gang, he sings to the prison guards:

You say I’ll get out early if I show you some repentance

But I ain’t never been too good at finishing a… (he trails off, distracted)

Jokes die on the operating table, but notice how much is going on here: a fab (implied) rhyme, an ingenious pun, and an unexpected gag to top it off. They say humour requires a dose of surprise — and this line has three.

(3) The Virtuosic Lyric – from “Right Hand Man” (Hamilton)

Say what you like about Lin-Manuel Miranda, the man can spin a zingy lyric.

I wanted to go for something a bit less well-known than Hamilton. There are, of course, amazing lines in In the Heights (I’ve always loved “Let me get an amaretto sour for this ghetto flower”) and Bring It On (“What, are you all scared? Y’all think cheerin’ is feminine? / Then I’m a feminist swimmin’ in women, gentlemen”). And 21 Chump Street is an underappreciated gem.

But take this, from “Right Hand Man”:

Now I’m the model of a modern major general,

The venerated Virginian veteran whose men are all

Lining up to put me upon a pedestal […]

It’s hardly an insight to point out that Lin is consciously building upon – and improving – a rhyme of Gilbert & Sullivan. (The original: “I am the very model of a modern major general. / I’ve information vegetable, animal and mineral.”)

Notice how much he achieves – not just theatrically but meta-theatrically – in this one line. He acknowledges a (white, European, semi-operatic) ancestor of contemporary musical theatre. It’s an ancestor that valorises perfect rhyme but, in this case, doesn’t quite achieve it. Lin corrects the rhyme by substituting in the right vowel: “mineral” becomes “men are all”. And suddenly the rhyme is mosaic (i.e. spread across multiple words), underlining its newfound ingenuity.

And consider the rhythm. The first line, as in The Pirates of Penzance, is square; it’s patter. The second – Lin’s addition – is syncopated, throwing the emphasis on unexpected beats; it’s rap. Together, they form a microcosm of an art form evolving.

Lin isn’t just nodding to the repertory. He’s announcing that he can go toe-to-toe with the masters and beat them at their own game – while signalling that it’s a game he intends to change.

He does a similar thing at the beginning of In The Heights. The show opens with a son clave – a rhythm played on a pair of claves that’s the essence of Afro-Cuban music and associated with Latin music in general.

Bernstein and Sondheim’s “America” from West Side Story begins the same way. That song is the result of two white New Yorkers (to be clear, geniuses) writing Puerto Rican-inspired music, to be sung by Puerto Rican characters, offering a Puerto Rican perspective on mainland America – although, as Sondheim confessed, they had never met a Puerto Rican. (Also a song in which the character sings, inaccurately: “Puerto Rico / You ugly island, / Island of tropic diseases”.)

Suffice it to say, I suspect the beginning of In The Heights is more than just a homage; it’s a reclamation. That’s not to imply any hostility; Lin famously had a loving relationship with Sondheim, characterised by warmth and mutual respect. At the same time, he has often talked about how the only parts available to him, as a young Puerto Rican actor, were the gangsters of West Side Story – and how he consequently felt the need to write himself and his compatriots onstage.

(4) The Subtextual Lyric – from “Unexpected Complications” (album Ahead of My Heart by Steven Lutvak)

Steve Lutvak was a dear friend and mentor to me. I’ll never forget the day he sat at the piano and played this song in class. We knew him as the soigné composer-lyricist of A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder – a pastiche-stuffed, hilarious, campy musical that won the Tony in 2014. (He and I had bonded over British vs. American rhymes.) But this was our first time hearing his true voice.

The first chorus runs:

And you say that I’m an unexpected complication,

And you smile when you say it, and I say, “So are you for me.”

Is anybody simple? Well, no-one at this table.

But here you are,

And here am I,

Nothing more to say except “We’ll see”.

A cardinal rule of writing a theatrical love song is that it can’t contain the words “I love you”. Instead, a character has to find a way of expressing that feeling in their own way. (Hence Henry Higgins’s “I’ve grown accustomed to her face”, in which we see a crotchety old man attempting, and failing, to resist inner growth.)

Steve’s solution is terrific. The setting is a second date. The singer and the man he’s interested in are at a restaurant, and it’s going well. Neither of them is new to the game, and yet they’re surprised and thrilled at how much they like each other. But it’s early days, and they know the ropes, and they obviously can’t say “I love you”. So instead they say “You’re an unexpected complication”.

I love the indirectness of the line – the tentativeness, the vulnerability, the gradual emergence of dormant emotions. We learned afterwards that the song is based on a true story. Art imitating life.

(5) The Economical Lyric – from “Being Alive” (Company)

Yes, it’s screamingly obvious. What am I meant to do? Leave Sondheim off the list?

Of course, the real difficulty lies in picking a single Sondheim song. How do you choose between “Finishing the Hat”, “Children Will Listen”, “Sunday”, “Losing My Mind”, “Not a Day Goes By”, and two dozen more of the subtlest and most profound songs ever written?

Here’s the final section of “Being Alive”:

Somebody crowd me with love.

Somebody force me to care.

Somebody make me come through.

I'll always be there,

As frightened as you,

To help us survive

Being alive

Being alive

Being alive.

“Help us survive / Being alive” – it’s as good as a lyric gets. The cynicism, the prayer, the longing for love, the recognition that marriage is not a panacea – all in eight syllables. Not just the craft but the ambivalent emotions behind it are typically Sondheim.

The great man annotates this song in Finishing the Hat with the following comment:

‘Chekhov wrote, “If you’re afraid of loneliness, don’t marry.” Luckily I didn’t come across that quote till long after Company had been produced. Chekhov said in seven words what took George and me two years and two and a half hours to say less profoundly.’

The Chekhov line is fab. But Sondheim compresses both cynicism and desperate hope into five words. And he makes it rhyme.

(6) The Pastiche Lyric – from “’Allo, Bonjour Monsieur” (album Charm Offensive by Fascinating Aida)

Fascinating Aida are a British national treasure. For decades now, they’ve lit up the cabaret circuit with their filthy and fabulous songs (more than one of which has gone viral).

I grew up listening to these kinds of witty, stand-alone songs (Flanders & Swann, Tom Lehrer etc.) and I take inspiration from them in my own writing. One song from Come Dine With Me was a minor homage to a Fascinating Aida song titled “’Allo, Bonjour Monsieur”.

“’Allo, Bonjour Monsieur” is a perfect example of our national sport: poking fun at the French. The singer – une femme de la nuit – riffs with the audience (“Madame! Yes, you. Red top. I told you last night: zis is my patch!”). Then she launches in earnest into her song, a paean to the virtues of safe sex.

It’s a masterclass in working an audience – a pinch of Franglais, a feast of terrific jokes, a syrup of heavy Gallic accents. There’s a lovely running pun on the word “johnny”. One thing they do especially well is to circle around the subject matter, hinting at but never quite saying the dirty word – until, like a magician’s final flourish, they shatter the taboo and declaim it triumphantly.

The whole song is great but here’s my favourite bit:

Where is your johnny now, Johnny?

Don’t be a tease.

Don’t blame me if I don’t want

A nasty disease.

It’s a good tactic,

Just one prophylactic

In your pocket, just for luck.

So if for me you’re desirous

Remember zee virus

Before you come… unstuck.

“Unstuck” is genius.

(7) The Lyric that Makes You Think – from “Seeing You” (Groundhog Day)

A hill I will die on is that Groundhog Day is one of the smartest, funniest, most moving musicals in the canon. Tim Minchin is at the peak of his powers, stitching together rock ’n’ roll riffs, folky small-town chorales and zesty pop numbers into a superb “theme and variations” score.

It’s also a tour de force of slant rhyme (about which I have thoughts). It’s easy to use slant rhyme the same way you might use perfect rhyme, and the effect can be underwhelming. But what songwriters like Tim Minchin and Anaïs Mitchell do so wonderfully is to teach the audience to listen in a different way.

Still, the lyric I want to highlight isn’t memorable for its rhyming but its construction. It comes from “Seeing You” (another absolute belter of a finale).

I thought I’d seen it all,

Was sure by now I knew this place.

I swear that I knew every hair,

Each line upon your face.

I thought the only way to better days was through tomorrow.

But I know now that I know nothing.

For my money, this is how a lyric can most effectively be “poetic” – not by using elevated language or dense imagery, but by throwing up unexpected ideas and insights that linger long in the mind.

“I thought the only way to better days was through tomorrow”: it doesn’t just beautifully distil a complex emotion we’ve all felt, it also tells us something about the singer. He’s grown; he now knows better; he’s gained some self-awareness.

Sometimes lyricists give implausibly clever or wise lyrics to characters who would never naturally say them. (Witness Sondheim on “I Feel Pretty”.) But in this case, the wisdom is the point – of the song, the character arc, the show.

(8) The Lyric that Tells the Truth – from “Julia, Julia” (album The Bridge by Benjamin Scheuer & The Escapist Papers)

This whole song is so plain and perfect that it feels churlish to single out any one line. Listen to the whole thing.

Notice how simple it is. There’s no hook. There are no multisyllabic rhymes; in fact, not too many rhymes at all. The melody follows a similar contour again and again (until it breaks the pattern on “Follow your heart and your head”, just like the breaking of a lover’s voice and heart).

Isn’t it a miracle? It tells a story; it tells the truth. Steve Lutvak used to say that lyricists have to “mean it”. It’s the simplest thing to do, and the hardest.

(9) The Lyric that Conceals its Message – from “I Can Do Better than That” (The Last Five Years)

The Last Five Years is a fan favourite, but I think this number goes underappreciated. For me, it’s maybe the most heart-wrenching song in the canon.

It doesn’t seem so at first. On the face of it, “I Can Do Better than That” is a bright story song in which Cathy recounts her romantic misadventures over a jaunty groove. She doesn’t regret any of these false starts; she always knew she could do better.

Then the song shifts into the present tense and she starts singing to Jamie, the person she thinks is her soulmate. She’s cynical no longer; now she’s bouncing with excitement and infatuation and hope. And at the very end of this five-minute song, she finally lays her cards on the table:

Think about what you wanted.

Think about what could be.

Think about how I love you.

Say you'll move in with me.

Think of what's great about me and you,

Think of the bullshit we've both been through,

Think of what's past because we can do better — we can do better than that!

And suddenly we understand. The whole reason she’s singing isn’t just to regale him with stories of old flames; she’s trying to pluck up the courage to ask him to move in with her.

And the effect is heartbreaking because we know her hope is utterly misplaced. Their love is doomed. We’ve just witnessed Jamie in bed with another woman. But, in the show’s non-linear structure, Cathy is at the beginning of her story, and hasn’t yet undergone the disappointments, humiliations and heartbreak that await her.

So the song conceals its message twice over. In the first place, Cathy takes a deceptively circuitous route to saying what she wants to say. Yet, more fundamentally, the song’s subtext actively undercuts its ostensible message. The tragic truth is that Cathy won’t do better, at least not this time.

(By the way, if your left ear ever wants a 90-minute masterclass in theatrical songwriting, Jason Robert Brown talks about this line, and much more, in this video. I watch it every year or two. There’s a ton of – how to put it? – unsugarcoated wisdom there.)

(10) The Beautiful Lyric – from “Something Right” (album The Sweet Spot)

This is probably my favourite lyric of all time. It’s witty, economical, truthful – but its real power goes beyond craft. I love it because, in so few words, it evokes such a warm and generous sense of life itself.

I thought that I could do nothing wrong

Until I did something right.

How much is contained in those two lines? An entire arc. A young person living a big, reckless, shallow life – until, almost by accident, they stumble across something of real value. It’s the end of youth and the beginning of adulthood. Suddenly they have something to lose, something to ground them.

It’s made all the more profoundly moving when you know the story of the songwriter, Fergus O’Farrell. (I learned about this from a former professor, who also introduced me to the song.) O’Farrell was an Irish singer-songwriter who led the band Interference. His songs were the basis of the movie, and later musical, Once.

He also suffered from muscular dystrophy and died at 48. “Something Right” was one of the last songs he ever wrote. It was released after his death.

Listen to his singing voice. You can detect the effects of his illness (which was degenerative and restricted his breathing). But you can also hear the love.

Think this list is terrible? Send me hate mail! (And/or sign up for my very infrequent newsletter.)

23 Anecdotes from 2023

Highlights from the year I became a bit more American

Highlights from the year I became a bit more American

1. Anna and I usher in the New Year at the Bronx Botanical Gardens! (Side-note: I have endless respect for the BBG’s gloriously maximalist, semi-incoherent approach to winter festivities. They run an exhibition featuring hundreds of miniature NYC landmarks, made entirely out of materials you might find in a forest… combined with a set of model electric trains running continuously… followed by an outdoor light show… with a guest appearance from a former world-class speed ice sculptor?!)

2. Come Dine With Me: The Musical has a brief workshop then a series of performances at The Turbine Theatre as part of the MTFest. My green card hasn’t arrived, so I can only join rehearsals via Zoom at 5am every day. It’s a stressful time, but the whole team is just magnificent. We sell out every night and get some lovely standing ovations. (Hopefully some spicy updates to follow in 2024!)

3. …and then my green card – incredibly, inevitably – arrives less than an hour after the final performance.

4. Anna and I celebrate our first wedding anniversary! Some friends and family have written us letters that we weren’t allowed to open until now, so we have a fabulous breakfast reading them aloud, before hopping on a train for a lovely long weekend in freezing Philly.

5. Joy and I start working on Hairpiece for the American Opera Initiative. We get to visit Tom at his wigmaking studio to learn about the process and see him in action. It’s a cave of wonders: thousands of wigs, jaw-dropping stories, a place humming with ancient expertise.

6. Spring break! Anna and I go on our second American road trip. Last year was the Southwest; this year, we hit the South. New Orleans: a snapshot of a different America; European buildings; swamp raccoons and alligators in the bayou; jazz everywhere; an unexpected day helping Jean-Marcel put the finishing touches to his nganga outfit and then joining him for the St Joseph’s Day parade. Atlanta: MLK museum; Jimmy Carter Library; Human Rights Museum; gorgeous gardens at Piedmont Park. Charleston: boat trip to Fort Sumter; heartbreaking trip to the former plantation Middleton Place. Richmond: state capitol building; art museum; the ghostly White House of the Confederacy. Then a quick stop in DC, and home.

7. We revive Black Holes Like Donuts – with the same stunning cast and director – for Theatre Now New York’s SOUND BITES festival. Inspiring to see the piece receive a full production!

8. Ellie and Caleb come to visit. They stay with us for five days in NY, then we hop a bus back down to DC to spend a long weekend at my godparents’ house. Cue a stream of museums, Bananagrams, dodgy homemade cocktails and manic laughter.

9. Noah’s graduation! Very proud brother. And as always, I’m hit by a wave of phantom nostalgia for an undergrad experience I never had.

10. Eliza and I get flown out to Chicago for the Johnny Mercer Songwriters Project. A wonderful, often challenging week: new friends, inspiring mentors, lots of sushi, a couple of new songs, until I have to fly home for…

11. …the Magdalen Ball! The first one my ole alma mater has pulled off in seven years. Tons of all-too-real nostalgia as Anna and I don our gladrags and immerse ourselves in the ridiculousness of it all: open bars, dodgems, food carts, shisha, silent discos, everyone in penguin suits. (Incidentally: my first ever back-to-back all-nighters!)

12. A gorgeous summer. I feel very lucky to have my Green Card and be able to travel again.

13. Sperm makes the shortlist to be fully funded by the BFI. Emilia, Max and I have a great interview, but ultimately no dice. Rejection is never fun – but we brush ourselves off and start the long journey of raising money piecemeal.

14. Chelsea and Kyle’s wedding! My first time in (scorching?!) West Virginia. Harpers Ferry, roadside markets, foosball with the cousins. The most beautiful celebration. I get initiated into the secret Verdin family dance moves.

15. Steve Lutvak – my teacher, friend and sometime employer – dies very suddenly and tragically. He was the most generous, dynamic, fabulously indiscreet person you could ever hope to meet – and, of course, an amazingly gifted singer-songwriter. In the days and weeks following, I listen to his songs on repeat; Lenny becomes my most-played song of 2023.

16. Joy and I head down to DC for a workshop of Hairpiece at the Kennedy Center Studios. It’s my first time workshopping an opera – eek! The singers (all Cafritz Young Artists) are extraordinary, and the mentors are terrific. All in all, it’s a frenetic, difficult, invaluable week full of revisions and reversions. Very inspiring to see three new operas finding their feet.

17. Brooke, Carrie, Eliza, Anna and I make our annual pilgrimage to Harvest Moon Orchard for a day of apple-picking. A really fab day, group and tradition. (Eliza masters the apple cannon!)

18. 2023 is a year for experimenting in new genres. Obviously there’s the opera with AOI. But I also finish GameStop (my first TV pilot), and write most of a song cycle with Bela, and join the NYU opera lab, in collaboration with the American Opera Project.

19. Noah takes me to my first ever basketball game and we cheer on the Brooklyn Nets from Row Z. A narrow loss – still enjoyable despite paying $32 for two beers.

20. “Time Slows Down” from Black Holes Like Donuts makes the final of the Stiles & Drewe Best New Song Prize, and I fly back to the UK just in time for the event at The Other Palace. We don’t win, but the theatre is rocking and I feel very lucky to have such amazing friends.

21. Eliza and I are invited to Manhattan School of Music to hear students singing our work! A crazy talented bunch, and some fascinating group discussions.

22. Alex comes to NY for the second time, and we have a lovely weekend of museums, ice skating, and avant-garde theatre.

23. Lastly, a very happy Christmas spent in Luxembourg with Anna’s family. Long walks, mince pies, brandy butter, ping pong, ravioli-making, lots of love and the most wonderful company.

“ABC”

Or: An Idiot’s Guide to Dealing with Rejection

Or: An Idiot’s Guide to Dealing with Rejection

I had a couple of tough rejections last week.

That’s nothing new. I’m a disciple of the CV of Failures. I have folders crammed full of subfolders crammed full of sub-subfolders, containing materials for applications I’ve made, residencies I’ve gone for, awards I’ve sought. I almost never get them, and that’s fine. That’s the game.

At The Other Palace with Zizi!

But last week was hard, maybe because I felt like both opportunities were within reach. The first was the Stiles & Drewe Best New Song Prize Final. Twelve finalist songs were selected out of about two hundred entries, and performed live at The Other Palace in London. I flew back to the UK, grabbed a few hours’ sleep and made my bleary-eyed way to the theatre for a brisk rehearsal and tech. Our song, “Time Slows Down”, was performed by the splendid and splendidly named Zizi Strallen.

It was a wonderful night, masterminded by the celebrated British musical-writing duo George Stiles and Anthony Drewe and hosted by the fabulous Rob Madge. I was touched that a dozen or so friends shlepped out to support me. I met some phenomenally talented writers and said hello to some industry fixtures.

But as far as the competition went… no dice.

So you smile graciously and congratulate the winners and inwardly seethe a bit and go home to lick your wounds and get some sleep. Onwards and upwards. Next up was a chance to pitch an as-yet-unwritten musical to a large musical theatre institution, in the hope they’d wanted to commission it for their company of young actors.

Eliza and I had made it to a shortlist of five, and our interview was coming up. We were pitching a musical we’ve had on the backburner for a couple of years. It’s called The Debutantes, and it’s about the forgotten female codebreakers of Bletchley Park. We’ve developed it at the Leeds Conservatoire and the Johnny Mercer Songwriters Project, but it’s the kind of musical you can’t really finish without institutional support.

So… we prepared like hell. We designed a pitch deck, replete with a synopsis, character list, sample songs, development history and bios. We wrote out our pitch, anticipated questions and prepared answers. We prepared videos of our sample songs, sent everything to the panel in advance and printed hard copies of the pitch deck and lyric sheets to distribute in the room.

The time came, and the interview was terrific. It went just as well as we could have possibly hoped. I left walking on air, then made the long journey from Mountview to Heathrow to JFK to LaGuardia to Bangor, where my brother and wife picked me up and drove me to my godparents’ house, arriving in the early hours of Thanksgiving.

The email came later that day. They’d loved our interview and congratulated us on a great pitch, but they were going to give the commission to a different team.

So you write a gracious thank-you email and wish them luck with their upcoming season and inwardly seethe a bit and go on a walk to lick your wounds and eventually get some sleep.

How do you deal with rejection? Writers swim in rejection as fish swim in water, but that doesn’t make it easier to deal with. You can’t convince yourself that oh, it didn’t matter anyway or I don’t care about their opinion. It did matter; you do care. That’s why you tried!

There’s really only one psychological strategy I know that mourns the loss, honours the intent and boosts the spirits. It’s known as ABC: Always Be Closing.

It’s a salesman technique. A technique that involves always scanning the horizon for new prospects while trying to close on the current sale. Then, if the sale falls through, you think not only, oh well, onto the next thing, but also oh wow, isn’t this new thing exciting?

On the same day (Thanksgiving) that I got rejected from the NMTA commission, I got an email from ScreenCraft. Over the summer, I’d written a 30-minute TV pilot and submitted it for a couple of competitions. It’s a story about the GameStop short squeeze of 2021, when a basement-dwelling dropout catalysed a coalition of internet weirdoes to save their favourite video game store and raze Wall Street to the ground.

Anyway, the email informed me that, out of 2100 entries, my pilot has advanced to the semifinals.

I don’t remotely expect to get any further, but it was a welcome relief. And it reminded me to see the bigger picture, rather than wallowing in the immediacy of rejection. When I was back in the UK, I didn’t just get rejected. I also worked on other things. Aaron and I did a flurry of writing for Come Dine With Me and had semi-advanced talks with a producer. I met twice with a new collaborator – an animation director interested in adapting our short musical into an animated film and pitching it to some major streaming institutions. And I had funding discussions with a producer friend about realising a short film based on a screenplay I wrote in grad school (which itself made it to the shortlist of, but got rejected by, the BFI Short Film Fund).

I have zero doubt that many of these projects won’t come to fruition, but some of them will. (It’s usually the unexpected ones.) And in the meantime, ABC is the best self-help I know. Rejection is only harmful when it breeds resignation.

The Nitty-Gritty of Opera Libretti

A libretto isn’t a play, lyric or poem. So what is it?

A libretto isn’t a play, lyric or poem. So what is it?

(Edit, February 10 2025: For some reason, this blogpost has been getting a lot of attention in recent months. I wrote it in November 2023 and my thinking about opera libretti has evolved quite a bit since then. If I were to write it afresh now, I’d be less concerned with capturing a “universal theory of libretto-writing” and more embracing of a multitude of approaches; after all, composers have infinitely varied styles and a big part of a librettist’s job is to help a composer play to their strengths. All the same, I think the piece gets at some interesting questions, so I won’t delete it. I’m grateful to my mentors at American Lyric Theater and Experiments in Opera for helping me develop my understanding of this strange and shifting art form!)

Benjamin Britten, E.M. Forster, W.H. Auden: three artists from the 20th century, all gay British men, all titans in their fields – and all in different fields. Forster was a novelist and Auden a poet, and yet Britten the composer sought both out as collaborators. He wanted to write great operas, and he identified both writers as great potential librettists.

Forster and Auden took to the task very differently. Auden relished the chance to flex his versifying muscles; Forster wrote, with a touch of relief, “Luckily nothing has to rhyme”. The two operas that resulted – Paul Bunyan (1941, written with Auden) and Billy Budd (1951, written with Forster and Eric Crozier) – both start with prologues, but these prologues couldn’t read more differently.

Auden’s begins:

CHORUS OF OLD TREES

Since the birth

Of the earth

Time has gone

On and on:

Rivers saunter,

Rivers run,

Till they enter

The enormous level sea,

Where they prefer to be.

…while Forster/Crozier’s reads:

VERE

I am an old man who has experienced much. I have been a man of action and have fought for my King and country at sea.

I have also read books and studied and pondered and tried to fathom eternal truth.

Much good has been shown me and much evil, and the good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect, some imperfection in the divine image, some fault in the angelic song, some stammer in the divine speech. So that the evil still has something to do with every human consignment to this planet of earth.

The American Opera Initiative 2023-4 cohort looking colourful

Auden’s libretto reads like poetry – like a nursery rhyme, even. It opens with blisteringly tight rhyming couplets; it doesn’t have, or attempt to have, a great deal of depth or complexity. The effect is flashy, if a touch shallow.

Forster and Crozier’s libretto has the elevation of poetry, but, in its expansiveness and lack of metre, reads more like prose. There’s little attempt at economy – in fact, the expansiveness is the point. Form matches content; grand ideas are discussed in long sentences of mysterious, grand, old-sounding language.

Isn’t it interesting how both are seen as entirely legitimate approaches to writing an opera libretto?

When I got my first commission in 2021 (for a piece that coincidentally ended up playing at the Royal College of Music’s Britten Theatre!), I sat down and tried to figure out what some of the guiding principles behind writing a strong libretto might be. After all, even if you don’t want to follow every rule, it’s useful to know the rulebook.

And yet the only resources I could find were invariably “big picture”. I found plenty of useful material about three-act structures, The Hero’s Journey, dramatic irony etc. I learnt about the importance of crafting an outline with your composer in advance of writing a single word or note. (Opera, for better or worse, has a tradition of librettists working privately on finishing an entire draft, then handing over the pages to the composer and allowing them to set everything to music, also in private.)

But try as I might, I couldn’t find what I most wanted: some practical, sentence-level guidance on how to write a libretto that would be easy to set and easy to sing; something about the differences between a strong libretto and a strong musical theatre lyric, or how both might differ from a poem or a piece of prose; some tips on how to allow the composer express their voice while keeping a crackle of wit and wordplay in the text.

I want to dig a bit deeper into these questions. I want to analyse some examples on a granular level, and see what lessons they can offer to would-be opera librettists.

Klaxon alert: I’m absolutely not any kind of authority. I’m just someone trying to figure this stuff out. But this year, I’ve had the amazing good fortune of being an American Opera Initiative Fellow. With Joy Redmond, I’m writing another chamber opera, this one bound for the Kennedy Center in 2024. Most importantly, I’ve had the privilege of learning from some world-class mentors and teachers at AOI and NYU; I won’t embarrass them by naming them, but I’m grateful to them all.

Let’s try and unpick some of these lessons.

Libretto vs. Lyric

Needless to say, there’s no single formula for writing a libretto.

Some of the most splendidly successful modern libretti vary widely. As One (music by Laura Kaminsky, libretto by Mark Campbell and Kimberly Reed) unfolds through epigrammatic lines, threaded with repetitions and occasional rhymes:

HANNAH AFTER

I let the pen guide me,

My writing like a girl’s.

Generous loops,

Graceful swirls,

Expansive ascenders,

Crosses with curls.

By contrast, Fellow Travelers (music by Gregory Spears, libretto by Greg Pierce) employs highly dialogic lines that, if not sung, would be at home in a play:

TIM

Hiya, Francie! Tip-top news from the Hill. You heard me. Your kid brother’s got a fancy new job writing speeches for a Senator… Senator Potter. Thanks to a phone call from a wonderful new friend: Hawkins Fuller. His friends call him “Hawk.” We met at an endless boring party. He might be my first actual friend in this every-man-for-himself town. How are you both, and my incoming niece or nephew? You’re naming it Timmy, right? No matter the gender?

The speechlike quality of the sung lines is very funny! Alongside the rich, Puccinian lushness of Spears’s music, they feel playful and irreverent – reflecting the playfulness and irreverence of the character.

From our workshop at the Kennedy Center rehearsal studios

To complicate matters further: not only do many successful modern libretti differ from each other, they also often shift registers within themselves. As One at one point slips into a terrifying duet of sorts: Hannah After sings an account of being assaulted by a stranger, while Hannah Before speaks a list of murdered trans people. The clash of musicalised vs. unmusicalised text, story vs. reality, is viscerally horrifying; the libretto has line-breaks but the effect is relentless and overwhelming. Fellow Travelers, on the other hand, often shifts from mock-dialogic lines into gorgeous, lyrical arias. The contrast is the point: a day at the office is prosaic, a night with your lover transcendent.

So, when successful recent libretti vary so widely between each other and within themselves, what lessons (if any) can we learn?

I think the first important principle is that, unlike the lyrics of most musicals, an opera libretto must contain everything.

It’s a well-earned cliché of musical theatre that the characters sing when they are moved beyond speech. Opera writers rarely have that luxury; their characters sing pretty much whenever they have something to say. It’s not that you can’t have dialogue in opera (witness The Magic Flute); it’s that the operatic emphasis on vocal production, non-amplification and large orchestras often makes dialogue impractical or underwhelming.

Librettists, therefore, can’t rely on the musical theatre trick of having characters speak exposition and sing emotion. And in opera, there isn’t such a sharp distinction between prose and lyric anyway. Contemporary musical theatre, tied as it is to 20th century pop music, favours four-bar phrases, pulse, antecedents and consequents, consistent time signatures. Contemporary opera generally eschews such predictability. But a lyric’s “lyricness” is virtually inseparable from the music’s rhythmic predictability.

What does that mean? Consider the following lyric from the late, great Sheldon Harnick:

Matchmaker, matchmaker, make me a match,

Find me a find, catch me a catch.

Night after night in the dark I’m alone,

So find me a match of my own.

Of course, composer Jerry Bock didn’t have to set it in a sixteen-bar phrase. He didn’t have to let the rhymes land on the important beats. The text has a dactylic lilt, but he could have written music that was totally different. But in that case, the lyric and music would have been pulling in different directions. Certain features of the lyric that make it lyrical – the rhymes, the metre – demand a certain kind of musical setting.

On the other hand, imagine if Fiddler on the Roof had been devised as an opera. Jerry Bock might then have rejected this text as being too square. The lyric practically insists on a sixteen-bar phrase and a “tum-tee-tee-tum” flow. But an opera composer, interested in subverting rhythmic and harmonic predictability, could easily complain that these elements set unwelcome constraits on the yet-to-be-written music.

(That was my UK writing partner’s advice before I sat down to write my first libretto. He said he liked the kinks and curlicues of speech-rhythms; they would enable moments of musical interest. Seamlessly flowing lyrics are often good in musical theatre, but bad in opera. Weird, idiosyncratic speech-rhythms are often bad in musical theatre, but good in opera.)

And it’s not just the flow of theatre lyrics that make them distinctively lyrical; it’s their adherence to overarching rhyme schemes, distinctive metrical templates, recurring textual patterns. The predictability of these patterns – i.e. the “periodicity” – is part of what makes a theatre lyric sing, but is anathema to an opera composer.

Still with me?

To summarise so far: operas are often resistant to “lyrical” lyrics. Partly that’s because a libretto must do the prosaic work of establishing exposition, character, relationship dynamics – i.e. establishing the waters the characters swim in. (A theatre song, by contrast, is usually a moment of emotional escalation, a brief instant where characters are transported beyond their normal vernaculars and communicate more colourfully and eloquently than before.) In addition, lyrical lyrics demand certain kinds of predictable rhythmic settings that opera composers may find objectionable, or at least insipid. Operas tend not to favour song form; musicals trade in them.

So, then, what kind of text does opera favour?

It seems to me there are three features shared by many successful modern libretti.

Opera Loves Repetition. Opera Loves Repetition.

Musical theatre songs have hooks – moments where melody, rhythm and lyric fuse to create an ear-catching phrase that gets to the heart of the song, usually at the beginning or end of the wider passage. Good libretti often seek to achieve the same effect without engaging in the periodicity of theatre songs. This involves repetition. Take this example from As One:

HANNAH AFTER

Controlled…

Constrained…

It cannot betray me.

My teachers,

My classmates,

My family

Cannot know.

HANNAH BEFORE

A firm grip,

A taut wrist,

A watchful eye

Maintain

A controlled…

Constrained…

Constricted…

Cursive

As it should be.

As One has been the most produced contemporary American opera since its 2014 premiere

There’s a lyrical echo in “Controlled… / Constrained…”, but it’s a repetition, not a hook. The text is set differently the second time; both pitch and rhythm are changed. What do we learn from this echo? Well, first and foremost, the message is reinforced; not only is the key phrase repeated but the very fact of the echo gives an added sense of inescapability. This is arguably strengthened by the difference in musical settings – almost as if the melody can go where it may, but the truth of the words persists. And by declining to write the echo as a hook – by letting the phrase sit among short, irregular lines rather than fitting it into a metrical and rhyming template – librettists Campbell and Reed give composer Kaminsky a good deal of flexibility to word-paint as she sees fit. The result: plenty of room to play with harmonic and rhythmic expectations, and let the words sing out.

It’s the Economy, Stupid.

Opera libretti tend to be spare, not square.

They’re spare because they favour short, economical lines – lines that let the composer write expressively and expansively, rather than scrambling to set all the text. And they’re not square because they resist periodicity – repeating structures, obvious end-rhyme schemes, seamless metrical flow – in a way that allows the composer to set the text in unusual rhythmic and harmonic ways.

Hang on. Didn’t I just point to Pierce’s and Forster/Crozier’s libretti as models of the genre? And didn’t I draw attention to their expansiveness? Isn’t that the opposite of spareness?

Yes – because both libretti play masterfully with the balance between concision and verbosity. Sometimes the text is speechlike and sprawling, deliberately so. The librettists use this technique to create a variety of effects: humour, stillness, uncertainty, a sense of the everyday. But this kind of expansive writing is the exception, not the rule. As a glance at the libretti shows, Billy Budd and Fellow Travelers both generally deal in shorter, sparer lines, emphasising the moments of expansiveness. Once again, the contrast is the point.

It’s worth noting here that opera libretti have an interesting double nature. From a bird’s eye view, their nearest cousin is probably a play; both forms deal in character, stakes, wants, obstacles, relationships, dialogue, plot and so on. But on a sentence-by-sentence level, a libretto’s nearest cousin will often be a contemporary poem. Most modern poems shun metre, but are intensely aware of rhythm. They rarely use perfect end-rhymes, but they’re attentive to phonetics, echoes, slant rhymes.

In fact, I think the main difference between a poem and text for an aria is that the latter exists in time. A poem may be read and reread, mined again and again for deeper meanings and new resonances. An aria is heard by an audience once. If the meaning escapes them, something has probably gone wrong. A poet, therefore, has the freedom to cluster images and ideas together densely, while a librettist and composer must be careful to track how much an audience can understand on one listen.

Christopher Reid is a master of slant rhyme

Elevate, Elevate, Elevate!

Opera libretti are often written in elevated language.

That’s not to say a librettist should use archaic or highfalutin words. Elevated language is just a counterpart of the short, irregular line lengths, as well as the fact that the characters are singing, not speaking. (If they could just as easily speak, why write an opera?)

There are many ways text can be elevated. Most obviously, you can use a vernacular that goes beyond the everyday. You can have soliloquys. You can make the text epigrammatic and elliptical. You can deploy repetition and allusion. You can fill the text with metaphor and simile. You can make your characters speak with Sorkinesque sharpness, so that even if they use everyday words, their wit is striking and funny.

But one of my favourite ways of elevating text – which I think is possibly underrated? – is to give it a skeleton of slant rhyme. Slant rhyme doesn’t draw attention to itself, like perfect end-rhymes do. It can stay nearly invisible, while doing a great deal to strengthen and poeticise a passage. Take the opening lines of one of my favourite poems, by Christopher Reid, describing the moment of his wife’s death:

Sparse breaths, then none —

and it was done.

Listening and hugging hard,

between mouthings

of sweet next-to-nothings

into her ear —

pillow-talk-cum-prayer —

I never heard

the precise cadence

into silence

that argued the end.

Yet I knew it had happened.

Say it aloud. The intial perfect rhyme (“none/done”) has so much heartbreaking finality. And then the interplay of masculine and feminine slant rhymes gives the poem lilt, poise, structure, while throwing up irregular rhythms that would naturally appeal to a composer.

Doesn’t it suggest a musical contour? Wouldn’t it sing well?

The Grand Finale

Opera is a broad church. It encompasses five hundred years of work, and – despite its reputation as a fusty, old, elitist, European art form – at its best it’s flexible enough to accommodate wildly ambitious, innovative, diverse approaches. Opera can be electronic, jazzy, dialogic, pre-recorded, non-narrative (just ask Philip Glass, Anthony Davis, Du Yun). Opera houses are generally more comfortable mounting untraditional work than Broadway theatres.

All this to say – of course there are no hard-and-fast rules for writing an opera libretto. Any text can be a libretto if claimed as such. Run wild and be free!

I’ve suggested some principles that I think many successful modern libretti adhere to. First, recognise that your libretto – unlike most theatre lyrics – will likely need to contain everything you want to communicate, both the prosaic and the heartfelt. Be sparing with periodicity and song form. Embrace points of reference, little textual echoes, repetitions. Let your text err on the side of economy (although feel free to contrast this with more verbose passages). Consider using elevated language, whatever you decide that is. Experiment with short, irregular line-lengths and half-rhyme. Above all, give the characters a reason to sing, not speak.

Benjamin Britten turned many different kinds of writers into librettists

W.H. Auden and Benjamin Britten never wrote another opera after Paul Bunyan, and ultimately parted ways on bad terms. But Britten was nothing but grateful to Forster. “Apart from the great pleasure it has been, it has been the greatest honour to have collaborated with you, my dear," he wrote in a letter. "It was always one of my wildest dreams to work with EMF – & it is often difficult to realise that it has happened. Anyhow, one thing I am certain of – & that's this; whatever the quality of the music is, & it seems people will quarrel about that for some time to come, I think you & Eric have written incomparably the finest libretto ever. For wisdom, tenderness, & dignity of language it has no equals. I am proud to have caused it to be.”

This hints at the most important lesson of all. Auden was a dominating personality; Forster was sensitive and generous. The best libretto is one that springs from librettist and composer alike – not the product of one mind, but a shared vision. And it should evolve in the composer’s hands. The music will shape the text, just as the text shapes the music.

So find a collaborator you like and respect, and get to work.

Want to chat more about opera libretti? Get in touch! (And/or sign up for my very infrequent newsletter.)

2022: A Recap

525,600 minutes, 37 anecdotes

525,600 minutes, 37 anecdotes

Brand-new newlyweds.

The year starts with a bang. Anna and I go to icy Beacon for a long weekend. Mount Beacon is too frozen to climb, so I propose to Anna at the base instead. She says yes, and we’re so giddy and tearful that we put the ring on the wrong finger of the wrong hand. Then we go for Mexican food.

Wedding-planning. We find an absolute steal of a wedding dress: beautiful, inexpensive, a perfect fit. Congratulating ourselves on our savings, I accidentally blow my entire suit budget on a tie.

Wedding bells in New Haven. Far and away the most emotional day of my life. I more or less hold it together until Nell sings “The Luckiest”, accompanied by Noah on the piano. That wrecks everyone, including the splendid Justice Gerald. But somehow we make it through our wedding vows, and then we’re married and sipping champagne in a rooftop bar.

Immediately off to the Leeds Conservatoire with Eliza for a workshop of THE DEBUTANTES. I’m so hyped-up (and jet-lagged) that I don’t get a wink of sleep the night before we start. Breakfast with the wonderful Matt Bugg. The students are incredible: generous, funny, warm, crazy talented. We write a new song over the week and dedicate it to them.

Back in NYC, I get COVID. Very mild (this time). Still tutoring online.

On the third floor of the Venetian hotel, indoors, in the middle of the night.

Eliza: truly the pianist to my page-turner.

Anna’s off for Spring Break and we go on our honeymoon.

Santa Fe, NM, on Mikey’s suggestion. Unbelievably pretty: adobe architecture, piñon in the air, everywhere walkable. We go hiking. Anna pets a cactus and prongs herself. I learn about Native American art: John Nieto, R.C. Gorman. We go to saloons and drink margaritas. I write lots of postcards. Meow Wolf. I leave my bag on the bus (computer, passport, keys, everything) – total disaster. Anna phones public transit office: they intercept the bus and courier my bag back. On a Saturday! Won’t accept any money, so I write a 3000-word thank-you email to their boss to try and trigger a performance-related bonus.

Flagstaff, AZ. Seven-hour road trip; we love it. America is huge and the landscapes are magical. Daniel Zaitchik’s “When the Deer Come” becomes the music of our honeymoon. Flagstaff is a great studenty town: mountainous, snowy, a blend of old and new. Our AirBnB comes with a hot tub. We gorge on Indian food and I collapse from exhaustion. Next day: Grand Canyon. I literally gasp at the view. It’s like being on Mars. Hiking, eagles, elk, trailmix for lunch, lots of signs saying “KNOW YOUR LIMITS”. More astonishing landscapes on the drive home. Fish tacos for dinner, then puzzles and P.G. Wodehouse. Finally, Sedona. Rust-red earth, vortexes aplenty. Anna pets another cactus and prongs herself again.

Las Vegas, NV. The Hoover Dam is terrifying: a thin walkway over the chasm, alongside a highway. Baking heat, blasting noise. But the city itself is extraordinary. Fake Statue of Liberty, Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triomphe, Venetian canals on the third floor of a hotel! It’s so hot that we get a huge refillable frozen margarita to share (manna from heaven). We make plans to go to the last dollar-a-hand blackjack table on the strip; I spend the whole morning poring over apps, memorising tables (i.e. “should you split 9s when the dealer shows a 10?”). Anna sips a frozen margarita by the pool. When we actually gamble, she does miles better than me. Together, we lose a net $15 over two hours, making it by far the cheapest thing we do. Then the red-eye back to New York.

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER has a run in New Mexico. Eliza and I don’t get to see it, but it seems to go brilliantly.

Lots of visits, lots of theatre. Sarah and Lucy come on a mum-and-daughter whistle-stop tour, then Nell and Susie on a gals trip. We see the spectacular HOW I LEARNED TO DRIVE. (I recognise Paula Vogel in the lobby and breathlessly say hello.) Easter with the McCooeys, with dares hidden in Easter eggs. Anna and I see A STRANGE LOOP and ISLANDER (both terrific; ISLANDER makes me optimistic about British musical theatre). We doll up for the Prospect Theater gala.

I go on my first marches, including the Queer Liberation March. My friends are dressed in gorgeous glitter and leather. I’m hurrying from tutoring, so I turn up in a collared shirt. Never been so simultaneously over- and underdressed in my life.

THREE PENELOPES has a run in London. I’d written the libretto in January, then more or less forgotten about it. But the production values are amazing: a 14-person mini-orchestra, incredible singers from the Royal College of Music, a set to die for. I’m proud of it! The experience reminds me how much money there is sloshing around in opera, and how little in musical theatre.

Harry’s beautiful wedding in California. Old friends aplenty. I visit San Francisco for the first time.

COVID again. This time it knocks me flat.

I get a new commission! The most money I’ve ever been offered up-front as a writer.

Vongai and I lead a workshop at Rattlestick Theater – podcasts, audiodrama, life as an immigrant theatre-maker.

A quick trip to Mystic, CT, where Anna and I read her childhood novel (also set in Mystic) and watch Noah break rowing records.

Ten days dog-sitting at a beautiful lake house. Anna – not previously a dog person – falls utterly in love. I feel mildly jealous. Sun, swimming. Aaron and I finish the first draft of our new musical.

Off to DC for July 4th. Anna gets out for summer vacation, and we fly southwest again. The Rockies are magnificent. Pizza, pick-up soccer, long hikes, bluegrass, dancing. I try El Salvadorean food for the first time. Anna’s family arrives. Horse-riding, Georgia O’Keeffe, a near-death experience while canoeing, seeing Lucy sing at the Santa Fe Opera House, back to Meow Wolf. Max and Christina’s stunning wedding.

Miranda and I find a producer for our short film, Sperm.

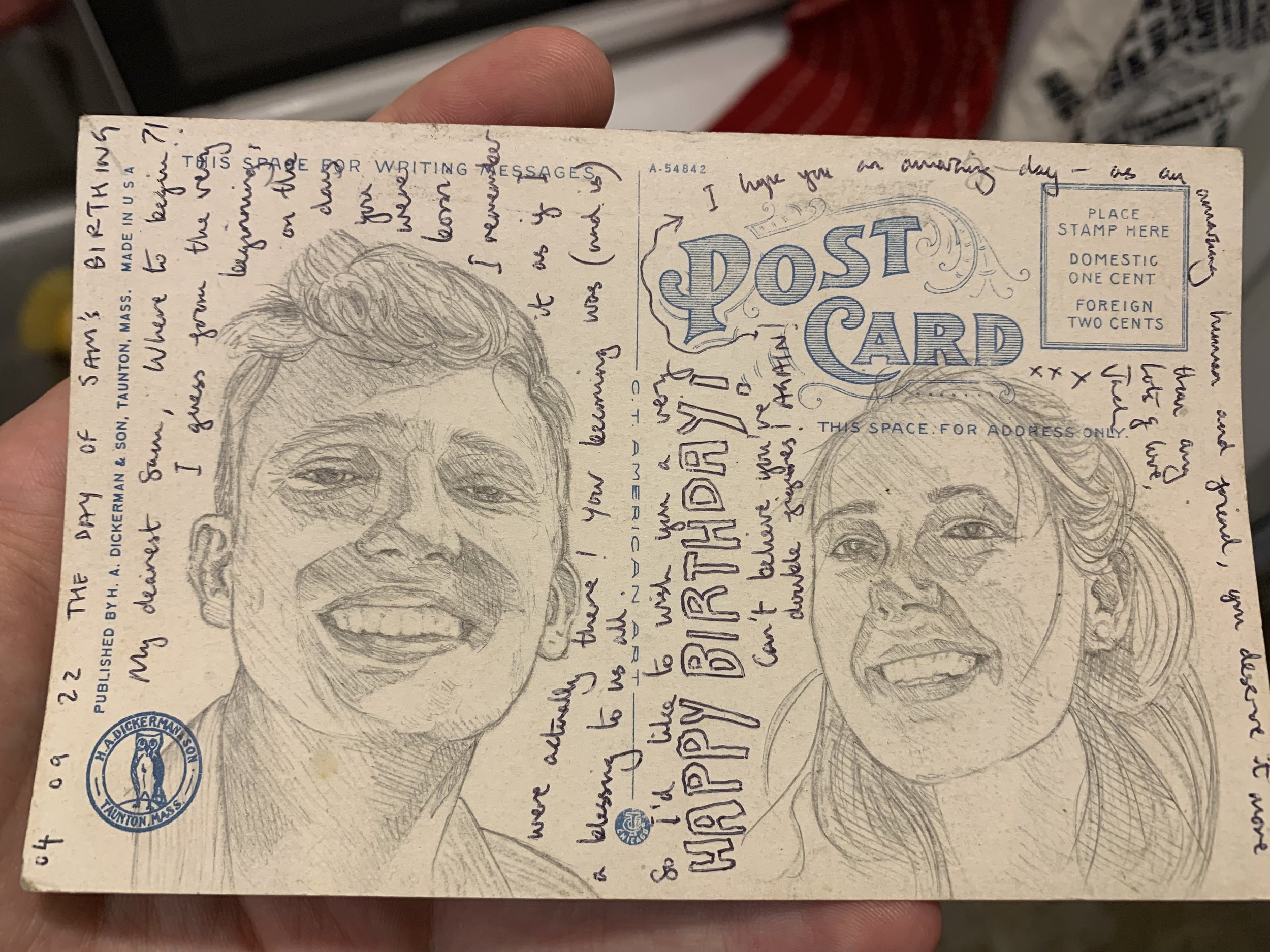

My birthday! Noah and Lindsey take me and Anna to Duelling Pianos the night before. Jack comes down from Yale with a hand-drawn postcard-portrait of me and Anna. Later, laser tag followed by a rooftop bar. My inner child is thrilled.

Bill visits from Amsterdam. We go to Coney Island only to find it closed, so instead we eat veggie burgers and wander up and down the pier, talking for hours. Later, we see Everything Everywhere All at Once with Erika, and the two of them really hit it off.

Sinan and Spencer have a gorgeous, colourful wedding celebration. They radiate happiness. I catch up with D over hors d’oeuvres.

Jack is also a fabulous illustrator.

Henry visits from the UK. His face lights up when we walk into Trader Joe’s. Mini-golf, the 9/11 museum, McSorley’s, comedy, sushi, tons of walking, TOPDOG/UNDERDOG (electrifying), a film night at Erika and Zane’s – then off to Boston. I’m lucky to have such amazing godparents. At the end of his trip, Henry insists on going to Trader Joe’s and buying two memorial tote bags.

I read “A Little Life” in advance of seeing the show with Anne. It’s an astonishing book. Reading it is like letting blood: painful, cleansing, exhausting, worthwhile. I just love it (although I don’t see the double meaning of the title until Anne points it out).

Erika, Mikey, Alex and Brandy host LUNÉVAL, an evening of rituals honouring the moon.

Aaron and I get some very good news about our new musical.

Carrie, Brooke, Emma, Anna and I go apple-picking at Harvest Moon. I feel very American, especially when operating the apple cannon.

Anna and I host a murder mystery party for Halloween, including full costumes and fight choreo.

Eliza and I speed-write a 10-minute musical, BLACK HOLES LIKE DONUTS, as part of the Prospect Theater Lab. It’s a joyous experience with a phenomenal group of people. The performance at Symphony Space gives me a weeklong adrenaline high. One of the highlights of my year.

I’m lucky enough to witness a developmental performance of YOKO’S HUSBAND’S KILLER’S JAPANESE WIFE GLORIA, written by Erika, Clare and Brandy. They’re the real deal.

See ya later, Grandmaster Carl.

Thankgiving in Virginia, with millions of Anna’s relatives. Big-hearted and brilliantly bonkers.

Lincoln Center debut. Eliza and I write a song for a BROADWAY FUTURE SONGBOOK concert, and it’s performed by the amazing Alyssa and Caitlin.

Chase hosts an Oxmas party, and somehow cooks a thousand lavish dishes in one regular-sized kitchen.

Nell and Mum come to America for Mum’s book launch. Helluva party, and a lovely long catch-up with Nell the day after. We go to the Union Square market for Christmas shopping. I play a chess hustler. Win two, lose two.

Anna and I watch England crash out of the World Cup with Tamanna and Anthony. We make consolatory mince pies.

December 18th is a good day. An epic World Cup Final in the morning with Noah, Lindsey and friends (Argentina win, thank goodness). A lovely long coffee with Carrie. Ice skating in Bryant Park with Bela, followed by veggie hot dogs and fries. Finally, Avatar in 3-D. The inner child is delighted.

Finger-lickin’ latkes at Maya’s!

My first Christmas in NYC, my first Christmas away from my family.

Please do say hello!

Things I Learned in the Chaos House

The Chaos House is dead! Long live the Chaos House!

The Chaos House is dead! Long live the Chaos House!

Between August 2020 and July 2021, I lived in a large, shabby, ridiculous, lovable, tumbledown house in Brooklyn with thirteen roommates. Ten of us were musical theatre students. It was loud. It was rambunctious. It was silly. It was the Chaos House.

How and why did we coalesce into such a sitcom-worthy living arrangement at the height of Covid? No vaccine had yet been invented, no restriction lifted. Rapid tests were vanishingly rare. It was a world of bubbles, travel bans and lockdown. The Chaos House arose in defiance. It was part artistic commune, part cri de coeur against an impending year of loneliness. Yes, we were in isolation, but dammit, we’d be in it together.

Two years later, the Chaos has dissipated and order has restored itself. It’s lovely to be back in a world of subways and theatre trips and real-life drinks with real-life people. But there’s a sense of loss too. The Chaos was awesome, magisterial, dynamic, an ancient despot forced to surrender his crown and old-world grandeur. Necessary perhaps, but not without its sadness.

I offer these lessons to any student of anthropology, any devotee of musical theatre, anyone flirting with the idea of group living in New York. But more than that, I offer them in the spirit of Alan Jay Lerner’s lyric:

Don’t let it be forgot

That once there was a spot

For one brief shining moment that was known

As Camelot.

For one brief shining moment there was also the Chaos House. I lived there. Here are some findings that should not be forgot.

Fortune Favours the Bold

The Chaos House was really two houses, or rather two apartments stacked on top of each other, connected via a door in the main hallway. Each of these apartments would naturally accommodate four or five, but had been retrofitted with fake walls to accommodate seven. Bedrooms ranged widely from the half-decent to the minuscule.

These apartments were not on the market. We discovered them through a realtor, who euphemistically described them as “fixer-uppers” in “Greater Williamsburg” (oh-so-suggestive of hipster bars and spin studios). In fact, they were in a roughish part of Bed-Stuy; we would face two break-ins over the next twelve months. To show us round, the aforementioned realtor actually had to break in, jimmying open the upstairs door with a credit card. The fridge was broken. Windows were shattered. No-one had lived there for years. The landlord offered us a deal.

Three weeks and four new roomies-from-Craigslist later, we were in.

A Lick of Paint Can Do Wonders

Our first task was to fix up our fixer-upper.

The Chaos House looked out onto a small jungle which pleased to call itself a garden. We enlisted friends (this was in the brief sweet spot before the second wave), assembled weed-whackers, and for a full day we wrestled with it. We pulled up weeds. We laid down gravel. We built a small fire pit.

The sun was scorching and it was sweaty, thirsty work. A kindly neighbour took an interest and brought us beer. (We grew very fond of him; he lived with his mother and enjoyed sitting outside with nothing but his thoughts and a joint.)

With the garden tamed, the upstairs roomies set about redecorating the upstairs. Soon the walls were painted – not a bland cream, but vivid reds and yellows, with epigraphs and artistic flourishes aplenty. (Two of the Craigslist brigade were architects with an impeccable eye for brushwork.)

Downstairs, we created a games room, filling it with squashy armchairs and stacks of board games. It was attached to The Dungeon. The Dungeon was the shadowy place where we rarely ventured – a dark, dank room in which we technically kept drums and mountains of storage, but which probably housed goblins and God knows what else.

Anyway, soon the Chaos House was a home. More than that, in a city of mass quarantine, it was a private members’ club. There was even an open-air tennis court nearby where we could sneak in at 7am and play a game before breakfast. We loved it.

Chaos Breeds Weirdness

Throw ten musical theatre writers, two architects, a game designer and a videographer together, and you get some strange habits forming.

It started with the shaved heads. Then there was the Self-Deprecation Jar. Then a select few of us started gathering for bedtime stories, where we would slip into character (I was Grandpa Christopherson, or “Grandpapa”) and read ghostly tales to the crackle of artificial fire on Youtube, only occasionally punctuated by ads for Grammarly.

After days of work, we would spend happy evenings getting drunk to the strains of Polish folk music. At Halloween, we acquired a pumpkin and then kept it until it went soft, at which point we used it as a drum. We held councils of war to discuss how to deal with the mice. Before it got too cold, we would roast s’mores outside and play ukulele songs. At the first snowfall, we devised makeshift toboggans.

Politically, we (predictably enough) fell anywhere between centre-left and Marxist. The night of the US Election, we all stayed up, getting gloomier and gloomier, until Trump declared victory and we went despondently to bed. The next morning, we woke up to an unexpectedly bright picture emerging of Nevada, Arizona, Georgia. A few days later, when Biden was announced as the 46th President, we found all Bed-Stuy literally dancing in the streets with joy.

Fourteen Roommates Go Big (Food)

Wednesdays were for Family Dinner, no arguing. We took turns cooking and introduced each other to our home cuisine: Hawaiian, Quebecois, Midwestern, Tex-Mex, British (a weak offering from me). We had a memorable fondue night.

Birthdays were not small affairs. The upstairs roomies had a whiteboard to help keep track. We held many a (bubble-preserving) party, hanging up piñatas and decorating the games room. We exchanged presents and prepared birthday banquets. One weekend saw five different home-made cakes.

We had two or three expert bakers in our ranks. An unexpected perk of living alongside them was being asked to cede the kitchen for an hour or two, then summoned to help with the “taste tests”. You got to wolf down a plateful of buttery pretzel bites and act like you were doing your friends a favour.

Fridge space was admittedly a problem.

Fourteen Roommates Go Big (Games Night)

After Family Dinners, we would often descend to the games room for a night of war by other means. Favourites included Catan, Betrayal at House on the Hill, and a cracking social psychology game called Wavelengths.

We also had a “Decathlon”, in which we split into teams and competed in various events. These included:

A spelling bee. (I tripped up on “camaraderie”. All those As!)

A freehand portrait competition using non-dominant hands.

A timed haiku competition.

Spikeball.

Group Rock-Paper-Scissors. (You conferred with your group, made a collective decision, then faced your opponents and bellowed “ROCK – PAPER – SCISSORS – SHOOT!” before revealing your move and prompting a wave of triumphalism and devastation.)

A smell test, using spices from the kitchen.

Pull-ups.

Timed song-writing.

I wish I could remember the other two.

Fourteen Roommates Go Big (Singing)

Ten of us were musical theatre writers. There was a lot of music.

When infection rates calmed down and my girlfriend was able to visit, she used to count the number of seconds between entering the house and hearing someone’s voice raised in song. It was never more than twenty.

If it all sounds really obnoxious, that’s because it probably was. But to us, it was a little niche of paradise. Different roomies had different (complementary) talents. Among us we counted a classical pianist, a jazz virtuoso, a guitar-player, a violinist, two drummers and a music producer extraordinaire.

So we collaborated on songs, recorded music videos, took online lessons altogether. Sometimes we’d have a karaoke evening or watch a movie musical (The Music Man and Inside were particular highlights). We learned as much from each other as from our professors.

And when, at the end of our grad program, it was finally time to present our finished shows to the whole student body and faculty, the ten of us gathered together to watch them on the large downstairs TV. Later that night, we cracked open several bottles of Prosecco and sang, to the famous Stephen Schwartz melody, “There can be MU-SI-CALS… when you belieeeeeve…!”

So Long, Farewell, Auf Wiedersehen, Goodbye

It was a glorious year. It could not last.

At the end of our lease, I left to move in with my girlfriend. Others left too. Some remained. But soon the house was populated with new roommates, and there was less singing.

The Chaos House had arisen as a rebuke against Covid, a refusal to be lonely. As restrictions began to lift, it had less reason to exist. Soon it felt like two apartments again, with little commingling between upstairs and downstairs – just two regular, inexpensive apartments without much in the way of privacy or maintenance.

Now the second year’s lease has ended, and almost all the original roommates have moved on. The downstairs belongs to total strangers. The garden and laundry are off-limits. Order has reasserted itself.

The Chaos House is dead. Long may it live in our hearts.

Care to share some chaotic thoughts of your own? Get in touch!

The Phonetics of Fascism

How does Sondheim temporarily turn us into monsters?

How does Sondheim temporarily turn us into monsters?

I recently wrote a blogpost about phonetics in lyric-writing, and another about the musical Assassins… so I thought I’d combine the two, and write about phonetics in the lyrics of Assassins!

(I promise it’s more interesting than it sounds.)

One of the great songs from the show is called “The Ballad of Booth”. If you haven’t listened to it, you’re missing out. It’s extraordinary. And in writing it, Sondheim set himself a challenge: how to depict John Wilkes Booth simultaneously as a racist murderer (as we see him) and a selfless, tyrant-slaying patriot (as he sees himself).

His solution is ingenious. For several minutes, we encounter Booth from the outside. The Balladeer attacks him as a raving narcissist and failing actor. But then Booth takes over the song. His music is stirring, nostalgic. The lyric is heroic and gentle.

And then it rises to an awful climax where Booth, in uttering a vile racist word, abruptly reveals his true colours.

It’s shocking. It’s meant to be. But what’s shocking isn’t just the force of the word, or the suddenness of the emotional reversal, but our realisation that we were momentarily wrapped up in Booth’s perverted worldview. Sondheim lulls the listener into accepting harmless-sounding premises, then brutally shows how they lead to an evil conclusion.

How does he manage it?

There are plenty of musical answers: the hymnlike chords, the crescendo, the sweeping orchestrations. And there are plenty of lyrical ones: the bucolic imagery, the swiftness of the mood-swing.

But Sondheim is also a master of phonetics – i.e. not just what the words say, but how the words sound. So let’s unpack some of his phonetic genius.

The (Relevant Bit of the) Lyric

How the end doesn't mean that it's over,

How surrender is not the end…

Tell 'em:

How the country is not what it was,

Where there's blood on the clover.

How the nation can never again

Be the hope that it was.

How the bruises may never be healed,

How the wounds are forever,

How we gave up the field

But we still wouldn't yield,

How the union can never recover

From that vulgar

High and mighty

*******-lover!

Never—!

Never. Never. Never.

No, the country is not what it was...

Damn my soul if you must

Let my body turn to dust

Let it mingle with the ashes of the country

Let them curse me to hell

Leave it to history to tell:

What I did, I did well

And I did it for my country.

Let them cry, "Dirty traitor!"

They will understand it later—

The country is not what it was...

What About It?

A quick general point. Some consonants are harsh, particularly labiodentals (D, T). Some are mellifluous, like fricatives (including V, F, SH, ZH), nasals (M, N, NG) and liquids (L, R).

Look at how Sondheim exploits this fact – the soothing liquids (healed/field/yield), nasals (surrender, end, never, again), and fricatives (over/clover, forever/never, recover). Read the lyric aloud to hear its silkiness. There’s hardly a prominent labiodental – aside from the bittersweet country – until high-and-mighty, which signals Booth’s descent into racist rage.

Notice, also, how the racist word follows a succession of -ver rhymes: over, clover, forever, never, recover. Only the vowels change. The endings are “feminine” – i.e. the final syllable is unstressed – so each rhyme fades gently away rather than being landed on. And the racist word is part of the rhyme scheme: we’re lulled by the softness of clover, forever, recover, and subsequently shocked by ******-lover.

In other words, the racism is inseparable from the twisted sense of patriotism.

It’s the climax, but not the end. Sondheim follows it up with more -ver rhymes: Never, never, never, never. (Reminiscent of King Lear?) And then we’re back in the warm phonetic bath of liquids (hell/tell/well), nasals (mingle, country), and fricatives (dust, must, ashes).

The only time we leave the bath is when Booth anticipates the response he’ll receive (“Dirty traitor!”). Each of the four syllables begins with a labiodental; the actor can spit out the words. So, in his own eyes, Booth is not only a gentleman, but a martyr — martyred by a benighted, vulgar world.

So What?

Lyric-writing – obviously – should never be academic. Sondheim didn’t sit down and consciously try to fill his lyric with particular phonemes. He just had a wonderful ear, and used it to match the lyric, the music and the mood.

Still, he clearly knew plenty about phonetics. On the famous opening line of Sweeney Todd, he writes:

“The alliteration on the first, second and fourth accented beats of ‘Attend the tale of Sweeney Todd’ is not only a microcosm of the AABA form of the song itself, but in its very formality gives the line a sinister feeling, especially with the sepulchral accompaniment that rumbles underneath it. If all of that seems like the kind of academic hyperanalysis which regularly shows up in studies of literary forms, I can assure you that even if the audience is not consciously aware of such specific details, they are affected by them.”

We’re affected in this song too – not only by what Booth says, but how he says it. Aided by the nostalgic music, he paints a picture of a warm, gentle “Southland”. He’s effective partly because his lyrics themselves sound warm and gentle. But then, out of this same sonic world, obeying the same soothing rhyme scheme, his violent prejudice reveals itself, embodied in a single wicked word.

It’s shocking because it’s unexpected. It’s ingenious because it reflects how racism permeates the seemingly warm worldview.

What can we lyricists learn?

Perhaps not too much. Only that Sondheim was an extraordinary writer (hardly a hot take), who paid close attention not just to what his lyrics said, but also how they sounded. And that the sound of lyrics should influence, and be influenced by, the sound of music. And that all aspects of a song are always (inescapably) interconnected.

Why Are Some Half-Rhymes Better Than Others?

Perfect rhymes are straightforward. Imperfect rhymes are hard.

Perfect rhymes are straightforward.

That’s not to say they’re easy; they often have to be dazzling, funny and memorable, and lyricists sweat blood to find the right one. But they work straightforwardly. You take a word like moon, and you substitute in new letters before the stressed syllable to find a perfect rhyme — like June.

Imperfect rhymes are hard.

They’re hard because there’s no formula for finding a good one. Certain websites do exist (e.g. the Rhymezone “advanced rhymes” feature, and also Double-Rhyme), but they’re far from exhaustive. You can’t just mechanically trawl through the alphabet, substituting in new letters at the beginning of the word. You have to use memory and imagination.

Why is this? Well, there’s only one way words can perfectly rhyme, but there are lots of ways they can nearly rhyme. Hop and hot are half-rhymes, but so are hop and hip... and hop and pot.

And weirdly enough, some half-rhymes just feel more satisfying than others.

Let’s see this in action. When you stick muggle into Rhymezone “advanced rhymes”, it offers the following suggestions:

chuckle

double

subtle

fungal

disgruntle

To my ear, those half-rhymes get worse – muggle/chuckle is better than muggle/double, but muggle/double is better than, say, muggle/disgruntle.

What’s going on here? Why are some half-rhymes better than others? How can we find good ones?

There are probably a million answers, but here are three.

1. Good Half-Rhymes Belong to the Same Phonetic Family

This is an incredibly basic fact to linguists and speech therapists, but I never really understood it – or the rhyming implications – until my mentor (and composer-lyricist extraordinaire) Pete Mills showed me. There’s also a brilliant article exploring this idea by Matthew Edward.

These phonetic families include:

Plosives: P, B, T, D, K, G

Fricatives: S, Z, SH, ZH, F, V, TH, CH, J

Liquids: L, R

Nasals: M, N, NG

Glides: W, Y

A “G” sound is closer to “B” than to “NG” – hence why muggle/double works better than muggle/fungal. Notice that “T” is also in the plosive family, so theoretically muggle/subtle should be about as good as muggle/double.

But it isn’t, quite, is it? That’s because even within these families, there’s a hierarchy of closeness. In fact, letters often exist in “voiced/unvoiced” pairs. These include:

G/K (guttural). These sounds are very similar, but you engage your voice on G and not K – so G is voiced, K unvoiced.

B/P (labial). B is voiced, P unvoiced.

D/T (labiodental). D is voiced, T unvoiced.

Gutturals are closer to labials than they are to labiodentals: try saying “Guh, Buh, Duh” to see how the sound moves forward in your mouth. That’s why muggle sounds closer to trouble than subtle.

But the question of voicing is also important. G and B are voiced, and T isn’t (hence why muggle/subtle isn’t so great). But what about T’s voiced equivalent, D? Muggle/huddle works better. Meanwhile, muggle/couple (P is unvoiced) is a little less good. Compare “a couple of muggles” with “a huddle of muggles” to see what I mean. The latter flows better. Voicing is important.

What about “voiced/unvoiced” pairs within fricatives? They include:

Z/S/ZH/SH. Z and ZH are voiced, S and SH unvoiced.

V/F. V is voiced, F unvoiced.

J/CH. J is voiced, CH unvoiced.